Manic Pixie Dream Girl

By Matt ZarzycznyI have a confession to make. I used to be Scott Pilgrim. And for the first time, I realized how bad of a thing that really is. Let’s back up a little bit.

Scott Pilgrim vs. The World is a film made by Edgar Wright in 2010, and it’s based on Bryan Lee O’Malley’s 2004-2010 graphic novel series, Scott Pilgrim. There will be massive SPOILERS ahead so if you haven’t watched Scott Pilgrim vs. The World or read O’Malley’s series, you’ve been warned. And really, do yourself a favor and at least watch the movie. It’s one of the most charming and visually stunning films of all time and features a cast that is full of today’s Hollywood elite (Aubrey Plaza, Chris Evans, Anna Kendrick, and Brie Larson all play minor roles in the film).On its surface, Scott Pilgrim vs. The World is the story of a slacker named Scott Pilgrim (Michael Cera) who is meandering through his Canadian life like any good millennial.

He has a band, Sex Bob-Omb, which no one really likes, he doesn’t have a job, he doesn’t really own anything other than his bass, he shares a bed with his gay roommate/best friend Wallace (Kieran Culkin) in a tiny apartment literally across the street from the house that he grew up in, and he’s dating a young girl (17) named Knives Chau (Ellen Wong). This is how we find Scott at the beginning of the film.

'manic pixie dream girl' An hour goes by and i started my work day, I was with a coleague and we were chit-chatting about our evenings and i decided to tell her about what happened in class this morning, she laughed and said ' That's weird. Manic Pixie Dream Girls have become more than just a fashion statement or a way of perceiving the world. Men have put something far more troubling onto the Manic Pixie Dream Girl: SALVATION. The Manic Pixie Dream Girl has somehow become a sexual Jesus to boring, suburban white men in their 20s and 30s.

He’s a young man in flux.A year prior to the events of the film, Scott went through a brutal break up with Envy Adams (Brie Larson) who is the lead singer of the now hugely popular band, Clash At Demonhead. Knives is the first girl that Scott has dated since the breakup, but he finds himself having to defend her status as a minor to all of his friends. Through these exchanges, primarily with Wallace and his bandmates Stephen Stills – the Talent (Mark Webber), Kim Pine – the Drummer and Scott’s ex (Alison Pill), and Young Neil – the Groupie (Johnny Simmons), we find that Scott doesn’t really like Knives all that much. They have a bit of a passive relationship with them mostly riding on the bus together and almost holding hands once.The opening credits of the film roll while Knives experiences Sex Bob-Omb for the first time and freaks out over how amazing she finds the band. We get to experience the budding relationship of Scott and Knives with her basically following Scott everywhere, doing everything that Scott wants to do (thrift store shopping, arcade game playing, music shopping, etc). You can really see the pedestal that Knives is putting Scott on, while Scott appears completely oblivious to the love that Knives is developing. This is absolutely necessary in the Scott Pilgrim story as it shows that his ego-centrism truly knows no bounds.

Scott’s needs and wants are fully front and center for him. Because he can’t afford to live on his own, he sleeps in the same bed as his best friend regardless of Wallace being engaged in his own sexual activities right next to Scott. It’s obvious that Kim and Scott did not have a great breakup, and she definitely harbors strong resentment towards Scott and his behavior, but he thinks everything is OK. Scott only sees what he wants to see in his life regardless of the people around him trying to make him take accountability for his actions. This is when Scott Pilgrim meets the girl of his dreams, Ramona Flowers ( Mary Elizabeth Winstead) who has 7 evil exes that Scott has to fight creating the plot of the movie. If you need more of a refresher, check out the.I’ve been a fan of Scott Pilgrim since the first time I read the graphic novels, and I was on the ground floor of the current cult status of the film.

I identified with Scott Pilgrim. I was a bass player in multiple mediocre bands, I was oblivious to the way that my behavior affected those around me, and I was also chasing the archetype of the Manic Pixie Dream Girl. I thought that I knew Scott Pilgrim. I figured out that the film was not really about Scott having to literally battle 7 evil exes, but it was actually about entering a relationship with someone and having to deal with their past. I think we’ve all been there at some point, where we find ourselves comparing who we are to who our partner has been with before.

Ramona’s ex-partners are definitely exaggerated to extreme proportions with her exes being everything from a famous skateboarder/movie star to a famous musician and even one of the hottest young music magnates. I understood this so well that I essentially went through it in a past relationship. An ex of mine was with a guy that literally tattooed his name on her in multiple places. It was a constant reminder of who she was with before.

There’s no way that I could physically compare to this guy. No matter how many times my ex would tell me how much better of a guy I was than him, I could never really get past the idea that she would rather be with pudgy, nerdy me instead of Mr. Partially due to the tattoos being a constant reminder, I really had a hard time making amends with her past, and this was one of the reasons why the relationship failed.That was my takeaway from Scott Pilgrim vs. The World: chase the Manic Pixie Dream Girl, overcome the exes that she has been with, and then live happily ever after. That is until recently.

I’ve entered into an incredibly healthy relationship and happened to revisit Scott Pilgrim. I’ve grown a lot since the last time that I watched the movie. I chased my Manic Pixie Dream Girl.

I fought her league of evil exes. But at the end of the day, I lost. So it’s with that life experience that I rewatched Scott Pilgrim vs. My reading of this film has completely changed: Scott Pilgrim is an asshole and Ramona Flowers is a screamingly hollow example of the Manic Pixie Dream Girl. The Manic Pixie Dream GirlIt’s hard to pinpoint when female archetypes are created. Some have very specific origins such as the creation of the blonde bombshell archetype by Hollywood in the 1930s, but others are more subtle in their creation.

There’s also a little bit of the “which came first” situation when it comes to entertainment and the creation of archetypes. The term Manic Pixie Dream Girl (MPDG) has its origin with film critic Nathan Rabin, who coined the term after observing Kirsten Dunst’s character in Elizabethtown. Rabin describes the MPDG as, “that bubbly, shallow cinematic creature that exists solely in the fevered imaginations of sensitive writer-directors to teach broodingly soulful young men to embrace life and its infinite mysteries and adventures.” While this kind of phrasing works great for stock characters, what Mr. Rabin forgets is that our society is obsessed with pop culture, and we tend to take what we see on screen and use it in our daily lives. This means that a whole generation of women that are unique, have strong opinions on music and probably color their hair in unnatural hues are being chased by men who envision them as this cinematic personification of the Manic Pixie Dream Girl. Why the Manic Pixie Dream Girl Archetype is DangerousI believe that all archetypes are dangerous as they remove individuality from us in favor of generalized group behavior.

However, at the end of the day, a lot of archetypes are fairly harmless. There are pros and cons of being a goth, a cheerleader, a soccer mom, a cougar, a jock, a nerd, etc. That apply to all genders in different ways. But look at those different archetypes.

They’re fairly simplistic and broad. The archetype of the Manic Pixie Dream Girl is incredibly specific in its scope. The true danger of it, though, is the quite ridiculous expectations placed upon women that fall into this archetype by the men that chase them. Manic Pixie Dream Girls have become more than just a fashion statement or a way of perceiving the world. Men have put something far more troubling onto the Manic Pixie Dream Girl: SALVATION. The Manic Pixie Dream Girl has somehow become a sexual Jesus to boring, suburban white men in their 20s and 30s. So now, if you have short pink hair, a witty attitude, a unique style and strong opinions, there is going to be a man (more than likely several men) who would sacrifice you on a cross to save their insipid, bland life.Aside from being martyred and discarded, Manic Pixie Dream Girls have to deal with men reflecting a lot of things onto them.

“Hey she’s wearing a Beastie Boys shirt, that means that we are into the exact same style of music, and I’m in love with her.” Unfortunately, this is the day-to-day life for Manic Pixie Dream Girls. For some reason, men see these very individual, unique women as blank canvases that they can put all of their interests onto. I never got this facet of the Manic Pixie Dream Girl problem. Why would men that are attracted to a woman because they are unique and interested in more obscure types of entertainment then want to completely ignore their interests in favor of the man’s interests?

I don’t get it, but it happens. Scott Pilgrim vs. The Manic Pixie Dream GirlIf Kirsten Dunst’s character in Elizabethtown defined the Manic Pixie Dream Girl, Scott Pilgrim vs. The World cemented it in the heads of everyone who watched it. Ramona Flowers is literally magic in the film and is used by Edgar Wright as a blank slate that Scott Pilgrim can put all of his dreams onto. From a cinematic standpoint, it’s ok that Wright used a Manic Pixie Dream Girl as a stock character in his script.

Unfortunately, the cult status of Scott Pilgrim keeps growing and more and more young women are starting to aspire to be like Ramona Flowers.Keep in mind is that Ramona Flowers is a stock character in a movie. Every real person in life is more than just a two-dimensional sketch of a character. Ramona Flowers is never given any real depth, and she definitely doesn’t exist as a three-dimensional character. I guess what I’m saying is that you can aspire to look like Ramona, to do your hair like Ramona, to dress like Ramona, but due to the behavior of men with relation to Manic Pixie Dream Girls, prepare yourself for a lot of one-sided relationships where you’re going to end up used and discarded.There is a chance though that Edgar Wright was saying more with his portrayal of Ramona Flowers than just putting another Manic Pixie Dream Girl on the big screen. The Manic Pixie Dream Girl as a MacGuffinA MacGuffin is a term used for a plot device in a movie that is pursued by the protagonist (and often antagonist(s)), moves the plot forward, and is usually given little or no narrative explanation.

MacGuffins have existed for as long as storytelling with many people pointing out The Holy Grail in the Arthurian mythos as kind of the archetypal MacGuffin. In films, The Maltese Falcon is usually singled out as one of the classic examples of the MacGuffin. I personally like using the briefcase in Pulp Fiction when discussing MacGuffins, because it might be the most ambiguous MacGuffin to be featured in a modern film.

All that we know about the briefcase is that Marcellus Wallace wants it and whatever is inside of it, Jules and Vincent are willing to kill for it. Do a brief Google search for Pulp Fiction briefcase and you’ll find theories saying everything from the contents being the diamonds that were stolen in Reservoir Dogs (not likely true because the briefcase glows with a golden light when opened) to Marcellus Wallace’s soul, because Ving Rhames is wearing a band-aid on the back of his head which indicates that his soul was stolen. The beauty about the briefcase, is that according to Quentin Tarantino himself, it is literally just a MacGuffin. It’s nothing.

It’s irrelevant to the plot. All that you have to know is that it’s important to the characters. Every meaning put onto the contents is done by the viewer of the movie, not its creators. Quentin himself has also regretted making the gold-colored light come out of the briefcase, as it also makes people assume too much about the contents. As far as Quentin was concerned, having a briefcase with an orange light bulb inside just looked cool.Remember that men tend to reflect a lot of things on to Manic Pixie Dream Girls, much like audiences reflect their own beliefs and interests onto typical MacGuffins. This makes the Manic Pixie Dream Girl almost a perfect human MacGuffin, and I would argue that Scott Pilgrim Vs. The World uses Ramona Flowers, the Manic Pixie Dream Girl, as just that: a MacGuffin.

Manic Pixie Dream Girl Synonym

Take a look back at the movie. What do we learn about Ramona Flowers? We learn that she’s American. She has seven evil exes.

She moved to Toronto to get away from all of that. She works for Amazon.ca as a delivery person. She’s bisexual and changes her hair color on a whim. She seems to like a lot of different types of tea. She has issues with guys becoming obsessive over her, and she tends to buck societal trends. For someone that’s supposed to be one of the main characters of a movie, that isn’t a whole lot of information, and I dare you to find more hidden in the subtext.

Everything that we learn from her flashbacks regarding the evil exes is unreliable, as it’s clear that she exaggerates their relationships, unless you take a literal reading of the movie and believe that the characters actually have “mystic powers” and it’s not just a metaphor for sexual prowess or emotional development. My point is that we never even find out whether she likes Sex Bob-Omb.

We know nothing about her actual interests. Everything that we think we know about her, we put onto her.

We assume that she likes the same music as Scott. We assume that she likes the same food as Scott.

When put into comparison to Knives Chau, we see a fully developed character in Knives with interests, goals, a family life, a school life, a social life, etc. And we see a maybe two-dimensional character in Ramona that is just a fashion statement with changing hair. But, like any good MacGuffin, she drives the plot of the movie forward while the audience puts all of their own ideas and beliefs onto her. Is It On Purpose?If Edgar Wright intended on creating Ramona Flowers to be a MacGuffin due to her status as a Manic Pixie Dream Girl then, frankly, he is a cinematic genius and an expert satirist of our society. If, however, the opposite is true and Ramona Flowers is an accidental MacGuffin, then Edgar Wright is as bad as every guy that’s ever used and thrown away a Manic Pixie Dream Girl.

I think the key to unlocking this lies in the ending of Scott Pilgrim vs. The movie was shooting at the same time that Bryan O’Malley was writing the last book of the series, so although Edgar Wright communicated with O’Malley, the ending of the film was created by Edgar Wright, and it is different than the ending created by O’Malley, but mostly in complexity. The books in general give you a much more three-dimensional view of Ramona Flowers, and the ending in the book follows through on that. The ending of the movie, however, is only focused on Scott Pilgrim. Scott finds the power of self-respect for the first time and finally apologizes to the people in his life that he has hurt before battling with Gideon (the second time). After defeating Gideon, there is a real opportunity for the film to actually make a statement about Ramona Flowers and Manic Pixie Dream Girls in general, but I think that the movie completely drops the ball. At the end, Ramona starts walking away with the anticipation that she’s just going to move to a new city and start a new life this time unencumbered by the evil exes of her past.

Scott stops her from leaving and Ramona might give the most cringe inducing line of dialogue, because it fully reinforces the stigma of the Manic Pixie Dream Girl archetype. Ramona tells Scott, “I should thank you thoughfor being the nicest guy I ever dated.” Here’s the thing. Even if Scott Pilgrim, someone who I thoroughly believe to be a complete asshole, is the nicest guy she ever dated, that’s really not saying much. The evil exes that she gives timelines to are often during her high school years. If the evil exes are presented in the order in which Ramona dated them, we don’t even get to know anything about numbers 5 and 6, the Katayanagi Twins convinces her that they should give their relationship a fresh start. If you do a Google search on MacGuffin and Scott Pilgrim, I found one review that mentioned in passing that Ramona Flowers might be a MacGuffin.

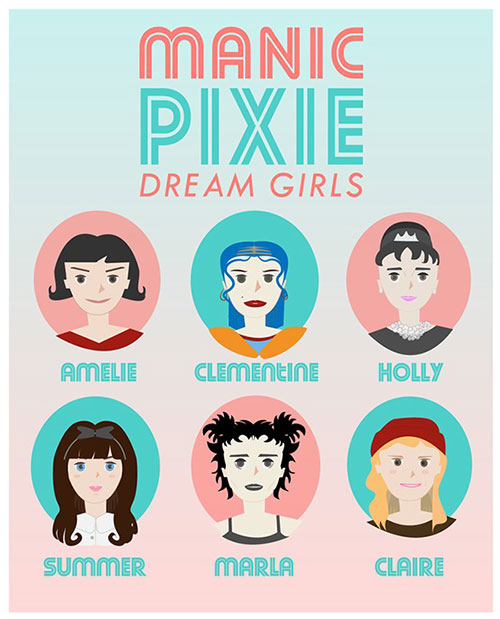

This doesn’t bode well for Edgar Wright. The Danger of the Manic Pixie Dream Girl ArchetypeAt the end of the day, I believe that Ramona Flowers joins the ranks of Manic Pixie Dream Girls of cinematic history. This history dates all the way back to the character Susan Vance, portrayed by Katharine Hepburn, in Bringing Up Baby (1938). There is a danger to this archetype, like any archetype, as movie characters are two-dimensional images created by writers that bestow whatever backstory they want onto their characters while real-world people are three-dimensional beings with real history and real emotions. At this point, it’s up to the male population to stop their obsession with the Manic Pixie Dream Girl. Being a young woman that finds themselves in the Manic Pixie Dream Girl archetype shouldn’t automatically mean that you have to deal with men using and discarding you just because of the way you dress or the kind of music you like.

Women should be free to be whatever they want. It’s time for the men of this world to stop being such Scott Pilgrims and instead treat every woman with the respect they deserve. I would be more reserved to hit out so hard at men liking MPDGs. As a teenager I loved the Idea of a Manic Pixie and yes in real life I have envisioned women that I dated as MPDGs but that didn’t make me discard them(, no matter how much of a bad way to think it was for the relationship).If anything it is the female oriented movies that have done a perfect job of creating 2-Dimensional heroes as perfect dates as in romcoms and most romantic movies.A majority of movies in the romance genre have the problem of making the opposite sex that they appeal to blank i.e.

Womens movies have blank males. Male movies have blank females.However most movies in the romance genre are and have (ever since titanic) been for women. Nowadays mostly written by them too.

And most definitely watched most exclusively by them.Many gender norms in dating have therefore been actually set by women.Maybe not through the creation of media, but definitely through its consumption.Like.

Like scabies and syphilis, Manic Pixie Dream Girls were with us long before they were accurately named. It was the critic Nathan Rabin who coined the term in a review of the film Elizabethtown, explaining that the character of the Manic Pixie Dream Girl 'exists solely in the fevered imaginations of sensitive writer-directors to teach broodingly soulful young men to embrace life and its infinite mysteries and adventures'. She pops up everywhere these days, in films and comics and novels and television, fascinating lonely geek dudes with her magical joie-de-vivre and boring the hell out of anybody who likes their women to exist in all four dimensions.Writing about Doctor Who this week got me thinking about sexism in storytelling, and how we rely on lazy character creation in life just as we do in fiction. The Doctor has become the ultimate soulful brooding hero in need of a Manic Pixie Dream Girl to save him from the vortex of self-pity usually brought on by the death, disappearance or alternate-universe-abandonment of the last girl. We cannot have the Doctor brooding. A planet might explode somewhere, or he might decide to use his powers for evil, or his bow-tie might need adjusting. The companions of the past three years, since the most recent series reboot, have been the ultimate in lazy sexist tropification, any attempt at actually creating interesting female characters replaced.

That Girl.Amy Pond was That Girl; Clara Oswald has been That Girl; River Song, interestingly enough, did not start out as That Girl, but the character was forcibly turned into That Girl when she no longer fit the temper of a series with contempt for powerful, interesting, grown-up women, and then discarded when she outgrew the role (‘Don’t let him see you age’ was River’s main piece of advice in the last season). ‘The Girl Who Waited’ is not a real person, and nor is ‘The Impossible Girl.’ Those are the titles of stories. They are stories that happen to other people. That’s what girls are supposed to be. Men grow up expecting to be the hero of their own story.

Women grow up expecting to be the supporting actress in somebody else's. As a kid growing up with books and films and stories instead of friends, that was always the narrative injustice that upset me more than anything else. I felt it sometimes like a sharp pain under the ribcage, the kind of chest pain that lasts for minutes and hours and might be nothing at all or might mean you're slowly dying of something mundane and awful.

It's a feeling that hit when I understood how few girls got to go on adventures. I started reading science fiction and fantasy long before Harry Potter and The Hunger Games, before mainstream female leads very occasionally got more at the end of the story than together with the protagonist.

Sure, there were tomboys and bad girls, but they were freaks and were usually killed off or married off quickly. Lady hobbits didn't bring the ring to Mordor. They stayed at home in the shire.Stories matter. Stories are how we make sense of the world, which doesn’t mean that those stories can’t be stupid and simplistic and full of lies. Stories can exaggerate and offend and they always, always matter. In Doug Rushkoff's recent book Present Shock, he discusses the phenomenon of “narrative collapse”: the idea that in the years between 11 September 2001 and the financial crash of 2008, all of the old stories about God and Duty and Money and Family and America and The Destiny of the West finally disintegrated, leaving us with fewer sustaining fairytales to die for and even fewer to live for.This is plausible, but future panic, like the future itself, is not evenly distributed.

Not being sure what story you're in anymore is a different experience depending on whether or not you were expecting to be the hero of that story. Low-status men, and especially women and girls, often don't have that expectation. We expect to be forgettable supporting characters, or sometimes, if we're lucky, attainable objects to be slung over the hero's shoulder and carried off the end of the final page. The only way we get to be in stories is to be stories ourselves. If we want anything interesting at all to happen to us we have to be a story that happens to somebody else, and when you’re a young girl looking for a script, there are a limited selection of roles to choose from.Manic Pixies, like other female archetypes, crop up in real life partly because fiction creates real life, particularly for those of us who grow up immersed in it. Women behave in ways that they find sanctioned in stories written by men who know better, and men and women seek out friends and partners who remind them of a girl they met in a book one day when they were young and longing. For me, Manic Pixie Dream Girl was the story that fit. Of course, I didn't think of it in those terms; all I saw was that in the books and series I loved - mainly science fiction, comics and offbeat literature, not the mainstream films that would later make the MPDG trope famous - there were certain kinds of girl you could be, and if you weren't a busty bombshell, if you were maybe a bit weird and clever and brunette, there was another option.And that's how I became a Manic Pixie Dream Girl.

The basic physical and personality traits were already there, and some of it was doubtless honed by that learned girlish desire to please - because the posture does please people, particularly the kind of sad, bright, bookish young men who have often been my friends and lovers. I had the raw materials: I’m five feet nothing, petite and small-featured with skin the color of something left on the bottom of a pond for too long and messy hair that’s sometimes dyed a shocking shade of red or pink. At least, it was before I washed all the dye out last year, partly to stop soulful Zach-Braff-a-likes following me to the shops, and partly to stop myself getting smeary technicolour splotches all over the bathroom, as if a muppet had been horribly murdered. And yes, I’m a bit strange and sensitive and daydreamy, and retain a somewhat embarrassing belief in the ultimate decency of humanity and the transformative brilliance of music, although I’m ambivalent on the Shins. I love to dance, I play the guitar badly, and I also - since we’re in confession mode, dear reader, please hear and forgive - I also play the fucking ukelele. Part of the reason I’m writing this is that the MPDG trope isn’t properly explored, in any of the genres I read and watch and enjoy. She’s never a point-of-view character, and she isn’t understood from the inside.

She’s one of those female tropes who is permitted precisely no interiority. Instead of a personality, she has eccentricities, a vaguely-offbeat favourite band, a funky fringe.I’m fascinated by this character and what she means to people, because the experience of being her - of playing her - is so wildly different than it seems to appear from the outside. In recent weeks I’ve filled in the gaps of classic Manic Pixie Dream Girl films I hadn’t already sat through, and I’m struck by how many of them claim to be ironic re-imaginings of a character trope that they fail to actually interrogate in any way. Irony is, of course, the last vestige of modern crypto-misogyny: all those lazy stereotypes and hurtful put-downs are definitely a joke, right up until they aren’t, and clearly you need a man to tell you when and if you’re supposed to take sexism seriously.

One of these soi-disant ironic films is (500) Days of Summer, the opening credits of which refer to the real-world heartbreak on which writer-director Scott Neustadter based the character of Summer' 'Any resemblance to people living or dead is purely coincidental. Especially you, Jenny Beckman.

Men write women, and they re-write us, for revenge. It's about obsession, and control. Perhaps the most interesting of the classics, then, is the recent 'Ruby Sparks', written by a woman, Zoe Kazan, who also stars as the title character. It’s all about a frustrated young author who writes himself a perfect girlfriend, only to have her come to life. When she inevitably proves more difficult to handle in reality than she did in his fantasy, the writer’s brother comments: 'You've written a girl, not a person.' “I think defining a girl and making her lovable because of her music taste or because she wears cute clothes is a really superficial way of looking at women. I did want to address that,” Kazan told the Huffington Post.

“Everybody is setting out to write a full character. It's just that some people are limited in their imagination of a girl.”Those imaginative limits, that failure of narrative, is imposed off the page, too, in the most personal of ways. I stopped being a Manic Pixie Dream Girl around about the time I got rid of the last vestiges of my eating disorder and knuckled down to a career. It’s so much easier, if you have the option, to be a girl, not a person. Cw cheats ppsspp.

It’s definitely easier to be a girl than it is to do the work of being a grown woman, especially when you know that grown women are far more fearful to the men whose approval seems so vital to your happiness. And yet something in me was rebelling against the idea of being a character in somebody else’s story. I wanted to write my own.I became successful, or at least modestly so - and that changed how I was perceived, entirely and all at once. I was no longer That Girl. I didn’t have time to save boys anymore. I manifestly had other priorities, and those priorities included writing.

You cannot be a writer and have writing be anything other than the central romance of your life, which is one thing they don’t tell you about being a woman writer: it’s its own flavour of lonely. Men can get away with loving writing a little bit more than anything else.

Women can’t: our partners and, eventually, our children are expected to take priority. Even worse, I wasn’t writing poems or children’s stories, I was writing reports, political columns.

I’ve recently been experimenting with answering ‘fashion’ rather than ‘politics’ when men casually ask me what I write about, and the result has been a hundred percent increase in phone numbers, business cards, and offers of drinks. This is still substantially fewer advances than I receive when I the truthful answer to whether I wrote was: “sometimes, in notebooks, just for myself.”I don't often write about love and sex on a personal level these days, even though I spend a great deal of time thinking about it, like everyone else in the It's Complicated stage of their twenties.

Lately, though, as I've been working on longer ideas about sexism and class and power, I keep coming back to love, to the meat and intimacy of fucking and how it so often leads so treacherously to kissing. I flick through a lot of feminist theory in the down hours where some people knit or go jogging, and I was prepared for the personal to be political. What I didn't understand until quite recently was that the political can be so, so personal.There was never a moment in my life when I decided to be a writer. I can't remember a time when I didn't know for sure that that's what I'd do, in some form, and forever. But there have been times when I didn't write, because I was too depressed or anxious or running away from something, and those times have coincided almost precisely with the occasions when I had most sexual attention from men. I wish I’d known, at 21, when I made up my mind to try to write seriously for a living if I could, that that decision would also mean a choice to be intimidating to the men I fancied, a choice to be less attractive, a choice to stop being That Girl and start becoming a grown woman, which is the worst possible thing a girl can do, which is why so many of those Manic Pixie Dream Girl characters, as written by male geeks and scriptwriters, either die tragically young or are somehow immortally fixed at the physical and mental age of nineteen-and-a-half.

Meanwhile, in the real world, the very worst thing about being a real-life MPDG is the look of disappointment on the face of someone you really care about when they find out you’re not their fantasy at all - you’re a real human who breaks wind and has a job.If I’d known what women have to sacrifice in order to write, I would not have allowed myself to be so badly hurt when boys whose work and writing I found so fascinating found those same qualities threatening in me. I would have understood what Kate Zambreno means when she says, in her marvellous book Heroines, I do not want to be an ugly woman, and when I write, I am an ugly woman. I would have been less surprised when men encouraged me to be politer and grow my hair long even as I helped them out with their own media careers.